The immediate recognition of the concussion is critical because repeated concussions pose a very real threat of death. There is evidence that athletes who suffer a second concussion before the symptoms of the first have healed are susceptible to a phenomenon called Second Impact Syndrome, or SIS15-16.

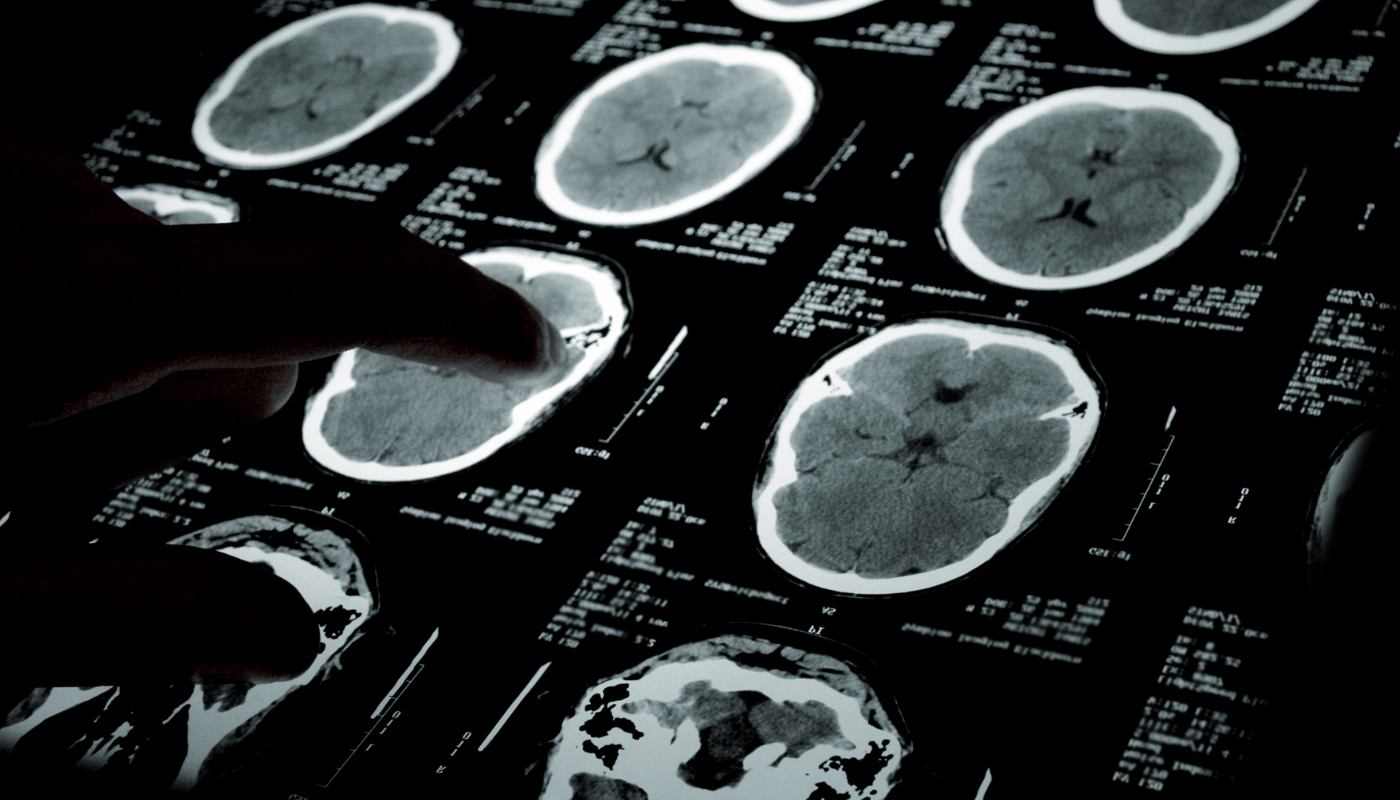

Though rare, SIS is characterized by rapid swelling of the brain. Surgery does not help and there is little hope for recovery. Most die, but those who live through SIS are often severely disabled. SIS is most often associated with athletes under the age of 19, perhaps because of the sensitivity of their developing brain and perhaps because the seriousness of the first concussion is often overlooked.

The first concussion does not need to be severe in order for SIS to occur. And, in many instances, it does not take a crushing second blow either to spark the onset of SIS. In fact, typically it is a subtle blow and it can occur days or even weeks after the initial concussion is sustained.

Second Impact Syndrome: An Idaho Story

Life changed for Idaho’s Kort Breckenridge on October 7, 2005. It was Senior Night, and the four-sport standout’s Teton High School Redskins were taking the field for their last home football game of the year. Despite suffering from the effects of a previous concussion, Kort was determined to play. “I’d vomit sometimes,” Kort recalled. “I’d hide it from my coaches. If the coaches had seen me vomiting they would’ve said, ‘No Kort, You can’t go back in (the game)’ so I’d hide it from them, and I’d tell my teammates not to tell them either. I wanted to play that bad.” Kort also hid the injury from his parents. “Kort told me he was okay and I believed what he was telling me. He had always been a very honest kid,” his father Ray Breckenridge recalls.

With symptoms still present from his previous concussion, Kort continued to play. And then, on Senior Night, Kort could no longer conceal the injury. After making a routine tackle, Kort struggled to his knees. Coaches pulled him out of the game and onto the sideline. Within minutes, he began seizing violently. Unconscious and unresponsive, Kort was transported to a local hospital where he was intubated and prepared for air transport to the nearest trauma facility. “He was just gasping for air,” Ray says. “He was fighting for every breath. You could tell he was fighting. But both pupils were blown. I thought he was going to die right there.”

By the next morning Kort had still not regained consciousness. Neurosurgeons inserted bolts into Kort’s skull in an attempt to relieve the massive swelling in his brain. His condition did not improve and Kort continued to lay comatose. Eight days later, doctors performed a craniectomy, a surgical procedure in which the entire right side of Kort’s skull was removed in an effort to relieve the intracranial pressure. “As soon as they did that, his brain just bulged out,” Ray recalls. “It had been in there just crying.” The outlook was grim. “Nobody – and I mean nobody – thought he was going to make it.”

Doctors kept Kort in an induced coma for the next two weeks. When he woke up, he was able to recognize his family, but it was obvious there was other significant brain damage. Kort remained hospitalized for the next three months. Little by little, with significant therapy, his conditioned began to improve. “He tells some very chilling stories about the experience,” Ray says. “Kort swears he talked to God. He said to me, ‘God wanted to know if I wanted to be with him or if I wanted to stay down on Earth… and I told God I had to stay on Earth to take care of my Dad.’”

Today, Kort Breckenridge continues his steady, slow process towards healing. His therapy continues. He has multiple scars, including a large cavernous furrow along his head. His speech is slurred. He walks with a slight limp and he tires easily. He has difficulty staying on task and his short-term memory is near non-existent. He will be this way – most likely – for the rest of his life.

Still, Kort hopes his story can help to inspire others. “If I had it to do all over again, I’d still play football,” he says, “but I’d just play it more safely. Even if I got just a light knock on the head, like just a buzz, I would tell someone. I definitely wouldn’t go back in the game.” Kort’s father, Ray, hopes others can learn from his experiences, as well. “It’s easy for people to blow it off,” Ray says. “It’s easy to say that ‘it happens all the time’ or ‘it’s just a dinger’. I just wish other parents could see some of the things I deal with everyday. Kort was always very driven. He was very popular. He had impeccable manners. He had a good sense of people. He was athletic and intelligent. He could sing, and he was very artistic. He was just one of those kids that could do anything he wanted to do. And now I see an entirely different person…somebody who struggles to get up in the morning… and to try remember how to do something really simple like cook an egg. He’s just completely different now. I wish parents could see that.”

See the New York Times video about Kort:

High School Football’s Hidden Danger: The Kort Breckenridge Story

Leave a Reply